This study:

- Showed that rats will forgo heroin and methamphetamine in favor of spending time with another rat.

- Highlights the importance of incorporating voluntary choice between drugs and social rewards in drug addiction research and introduces a novel model for studying the impact of social motivation in studies of drug use and addiction.

A recent study published in Nature Neuroscience shows that social interactions can have a profound effect on drug self-administration and relapse and on the brain’s response to drug-associated cues. The research was conducted in Dr. Yavin Shaham’s lab of the NIDA Intramural Research Program and was led by Dr. Marco Venniro.

The researchers gave rats the option of pressing one lever for a drug infusion or a different lever to open a door and interact with a social peer. The rats opted to open the door more than 90 percent of the time, even when they had previously self-administered methamphetamine for many days and exhibited behaviors that correspond to human addictive behaviors.

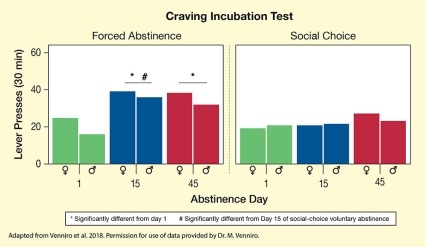

The researchers demonstrated differences between the rats that voluntarily forwent methamphetamine to obtain social reward and a group of rats that were forced to be abstinent when their access to the drug was removed. The rats that chose abstinence showed no signs of the intensification (incubation) of drug craving that happens over time both in rat models and in some humans who abstain from drug use. In contrast, the rats that were forced to be abstinent sought the drug more avidly 15 and 45 days after their last dose than they did on the first abstinence day (see Figure). The voluntary-abstinence rats’ lack of “incubation of craving” was associated with evidence of reduced neuronal activity in the central amygdala and the anterior ventral insular cortex, regions associated with drug relapse and craving in rat models.

Dr. Venniro says, “These results demonstrate that social reward has remarkable protective and restorative effects in rodent addiction models and illustrate the importance of considering social factors in neuropharmacological studies of drug addiction.” The model used in this study provides a tool for doing just that. Researchers can use it to learn how social rewards alter the ways that potential new medications or other factors affect behavioral and neurobiological responses to addictive drugs.

The ultimate objective of such studies will be to learn how social rewards might be used to prevent and treat human addiction. Social reward already functions as the principle of some evidence-based therapies. Dr. Venniro says, “From a clinical perspective, our findings support wider implementation of social-based behavioral treatments, which not only include the community reinforcement approach, but also innovative social media approaches, such as those being implemented to provide social support before and during drug-seeking episodes.”

Dr. Venniro notes that the social lives and responses of people are vastly more complicated than those of rodents. Accordingly, animal studies of the role of social reward in drug addiction will have to be meticulously designed and cautiously interpreted if they are to serve their purpose.

This study was supported by NIDA’s Intramural Research Program.

- Text Description of Figure

-

The bar chart shows the results of a craving incubation test in methamphetamine self-administering rats that were forced to remain abstinent (left panel) or voluntarily forewent methamphetamine in favor of interacting with another rat (social choice, right panel). The horizontal x-axis shows the results for female and male animals in both groups on Day 1 of abstinence (green bars), Day 15 of abstinence (blue bars), and Day 45 of abstinence (red bars). For each pair of bars, female animals are shown on the left and male animals are shown on the right. In both panels, the vertical y-axis shows the number of lever presses to obtain methamphetamine during a 30-minute test session, on a scale from 0 to 60.

In the forced-abstinence group, on Day 1, female animals had about 25 lever presses and male animals had about 15 lever presses. On Day 15 of abstinence, females had about 38 lever presses and males about 35 lever presses, and on Day 45 of abstinence, females had about 38 lever presses and males about 32 lever presses. Asterisks above the blue and red bars indicate that these values were significantly different from the values on Day 1 of abstinence, reflecting incubation of craving. The hash sign above the blue bars indicates that these values were significantly higher than those on Day 15 in the social-choice abstinence group.

In the social-choice abstinence group, on Day 1 of abstinence, females had about 19 lever presses and males had about 20 lever presses; on Day 15 of abstinence, females had about 20 lever presses and males had about 21 lever presses; and on Day 45 of abstinence, females had about 27 lever presses and males had about 25 lever presses.

Source:

- Venniro, M., Zhang, M., Caprioli, D., et al. Volitional social interaction prevents drug addiction in rat models. Nature Neuroscience. 21(11):1520-1529, 2018.