This video is part of the NIDA series At the Intersection: Stories of Research, Compassion, and HIV Services for People who Use Drugs.

NIDA supports research to better understand why people who use meth may be more likely to experience poor HIV outcomes and to discover effective ways to prevent and treat HIV in this population.

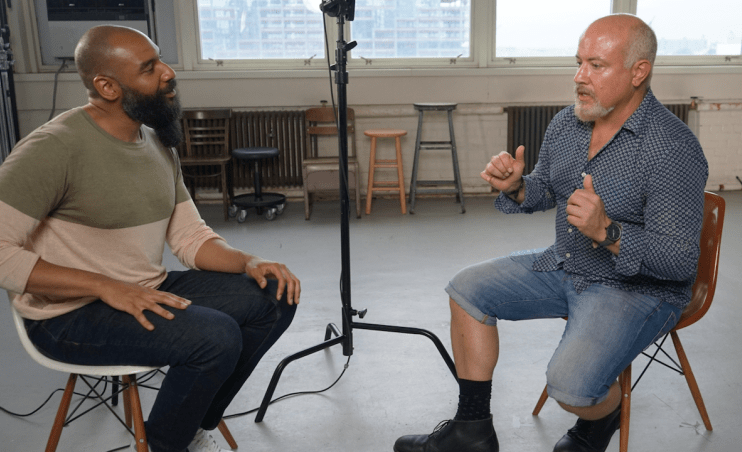

In this video, HIV advocate and artist Ken Williams speaks to Christian Gov, Ph.D., of the City University of New York (CUNY) School of Public Health, and Adam Carrico, Ph.D., of the University of Miami, about their NIDA-supported research on preventing and treating HIV among sexual minority men who use meth. Sarit Golub, Ph.D., M.P.H., of CUNY Hunter College, and people with lived experience at the intersection of substance use and HIV also share their insights on the ways stigma and other factors can impact access to HIV services.

Video length: 7:59

Transcript

[Dr. Adam Carrico] It's about time, right? We're almost 40 years into the epidemic and still grappling with how much it's interwoven with substance use.

[Ken Williams] Decades of research and community mobilization have ushered in incredible advances in HIV treatment and prevention. But to end the HIV epidemic, these advances need to reach everyone who needs them, including people who use drugs like methamphetamine.

In the past decade, researchers have seen higher risk patterns of meth use and meth-involved overdose increase in multiple US populations. At the same time, researchers who study HIV and substance use have found an increasingly tight link between meth use and poor HIV outcomes.

This is particularly true among sexual and gender minorities. One 2020 study estimates people who regularly use meth account for about one in three new HIV transmissions among sexual and gender minorities.

Dr. Grov and Dr. Carrico are working on NIH funded research to better understand how meth use among gay and bisexual men impacts HIV outcomes. So, I'm wondering–why are gay and bisexual men who use meth a priority population for HIV research?

[Dr. Christian Grov] The answer for that is you have to look at where the case numbers are happening, and you let the epidemiological data guide you. And I'm seeing numbers and rates of particularly methamphetamine use increasing in our communities at a time when we've had PrEP for a decade, and we're seeing a stubborn number of HIV infections in the United States that really isn't budging in light of this highly effective prevention tool.

[Williams] This highly effective prevention tool, PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, refers to medication that helps prevent HIV in HIV-negative people. So if the numbers aren't budging, despite this, how do we end the HIV epidemic?

[Dr. Sarit Golub] We can't end the HIV epidemic without understanding the totality of individual's lives.

[Williams] Can we hear that again?

[Golub] We can't end the HIV epidemic without understanding the totality of individuals lives. And I think a lot of times we segregate issues of substance use from other aspects of HIV prevention or for other aspects of health care. And what this really underscores to me is the extent to which this holistic approach, this really understanding human beings and their full experience is what we need to end the epidemic.

[Delano Burrowes] I realize how much of drug use and the addiction was really rooted around the fears of connecting to people and being myself and I started to have friends that cared about me for the first time, and I started to care about myself for the first time. And I realized this doesn't have to be the end of my story anymore.

[Williams] The researchers I spoke to explained that HIV and meth use are linked in several ways. Meth can cause changes in the body that may make it more vulnerable to HIV, and it can also influence sexual behavior in similar ways.

[Grov] The way that substances impact HIV, and I’m going to particularly focus on methamphetamine, is behaviorally. We see behavioral disinhibition for people that are using meth. If they're combining it with sex, they're going to have probably more partners, have more sex, have sex for a longer period of time, and condoms may be less likely to be used, if they're being used at all.

[Carrico] I think drugs and sex, especially for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, are a real cultural phenomenon that people are mixing drugs and sex for pleasure often to enhance sexual pleasure.

[Grov] When you come from a community where having sex with someone of the same sex is a really fraught experience that's looked down upon, combining that with something like meth can really improve the experience as well and help you not think about the aspects of it that might make you feel shame for doing it.

[David Marshall] Crystal meth for me has a lot to do with sexual, social, emotional loneliness. It satisfies a lot of different aspects of my life that continue to be at issue.

[Golub] And the question is, how can we make sure that those folks are kept as safe as possible within the context of that behavior?

[Burrowes] I remember the first time I did crystal meth, I felt sexy and I felt connected. I've never done meth without having sex.

[Carrico] And sometimes that can lead to outcomes they don't want, right? Like, having different types of sex or sex with multiple partners, and other times it can lead to a fun night. So, you know, it's really a wide array of different kinds of experiences that we see guys having when they're partying and playing.

[Williams] In this case, “partying and playing,” or “chemsex,” means using drugs as part of your sex life. Gay and bisexual men who party and play report doing so for a variety of reasons. Some say it makes them less inhibited and increases pleasure, or that they mix meth and sex to address issues in their sex life and self-esteem. So, how risky is this?

[Golub] The problem with risk is that—that's a public health term, right? And the minute that we put this risk frame on the conversation, it's alienating. And it makes an individual think that I am placing a judgment on that behavior by labeling it as a risk behavior.

[Burrowes] And it wasn't just like, “Hey, I'm doing drugs and I'm not going to have a condom.” It was like, “I don't want to have a condom.”

This is like the barrier to me connecting, the barrier to me being sexual. And this is a person I always want to be, and there's no consequences in my mind.

[Williams] People use meth for a lot of different reasons, and people who use meth may have a lot of different goals for their health and life—from staying safer while using meth to working towards long-term recovery from meth addiction.

[Burrowes] Was recovery the goal? The goal was just not to die. And I didn't know how to live.

[Carrico] People have all sorts of goals with regard to their substance use that we can help them meet. There are all sorts of ways that we can engage clients and participants in our research studies in setting goals for behavior change that really match their values and goals in that moment without demanding that they be abstinent to even receive the benefits of counseling. Complexity is the rule and not the exception of the lives of the men we serve.

[Marshall] I think that at the root of my pain is pain. But I know that the use of this drug exacerbates a lot of things, a lot of things that I’m aware of and a lot of things that I'm probably not aware of. I don't think that kicking meth is a solution to all my problems and that everything will just be fine. But I do think that it's one thing that's for certain that things will get better.

[Williams] How do we talk about HIV in a way that's inclusive of gay and bisexual men who are using drugs or even experiencing addiction? How can research help us see the light at the end of the tunnel where those in need are affirmed and validated in health care spaces? One way may be to close the research gap. You know, let's get a clearer picture of the totality of people's lives—from HIV to substance use and beyond.

[Voiceover] To learn more about substance use and addiction research, log on to nida.nih.gov.

If you or someone you care about wants help, you can learn more by calling the National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or by visiting FindTreatment.gov.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Accessed Oct 25, 2022.

- Grov C, Westmoreland D, Morrison C, Carrico AW, Nash D. The crisis we are not talking about: One-in-three annual HIV seroconversions among sexual and gender minorities were persistent methamphetamine users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(3):272-279. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000002461

- Salamanca SA, Sorrentino EE, Nosanchuk JD, Martinez LR. Impact of methamphetamine on infection and immunity. Front Neurosci. 2015;8:445. Published 2015 Jan 12. doi:10.3389/fnins.2014.00445

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Motivations associated with methamphetamine use among HIV+ men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(3):149-156. doi:10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00223-4

- Stanton AM, Wirtz MR, Perlson JE, Batchelder AW. "It's how we get to know each other": Substance use, connectedness, and sexual activity among men who have sex with men who are living with HIV. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):425. Published 2022 Mar 3. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-12778-w