From the printing press to AI chatbots, new technology has long enthralled humans. It can both terrify and excite us with its potential for vast change. For Brenda Curtis, disruption is the goal. A principal investigator in NIDA’s Intramural Research Program, Dr. Curtis uses artificial intelligence (AI), social media, and smartphone sensors to gain a better understanding of substance use and misuse. Among other goals, she aims to develop effective and accessible digital tools to help people in treatment or recovery for substance use disorders.

Q. Your recent study showed that AI can analyze Facebook posts from people in outpatient addiction treatment and predict whether they will complete their program. What kinds of clues did you see?

Language has meaning and tone and feeling attached to it. For this study, we collected two years of Facebook posts from each research participant before they entered treatment and used AI to look at the context of their language to predict the likelihood of leaving treatment early. Are they talking about friends and family? Are they talking about supportive environments? For example, we saw that participants—who were mostly men—who used language that referred to women in positive tones, which could indicate emotional support, left treatment less frequently than those who did not refer to women in positive tones. We found we could have predicted 79% of patients who did not finish the program. A treatment center could potentially use this tool to assess a person upon intake. It could give them some indication of who is most at risk of leaving treatment early so they can triage services better.

Q. What else can AI tell health professionals about patients?

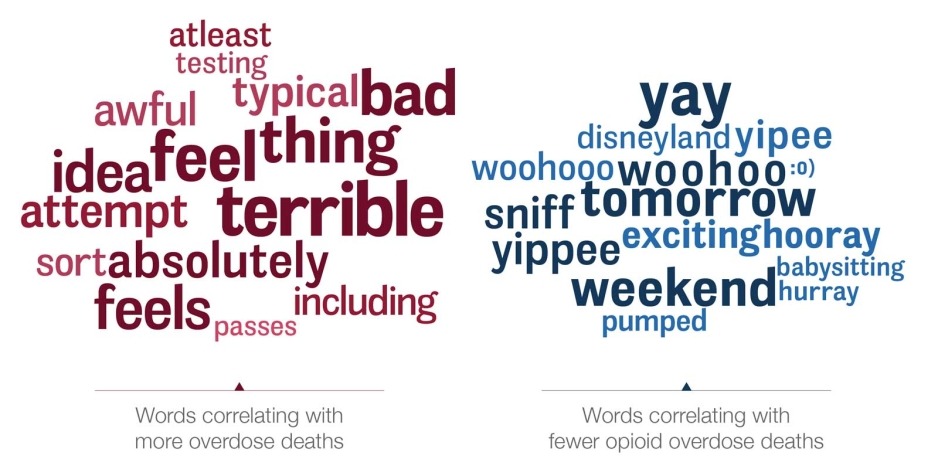

Language is a function of who and where we are. Substance use is very complex, and we have been using language to look at social vulnerabilities, such as a lack of emotional support. We have also looked at depression and anxiety as well as environmental influences such as quality of life, uncertainty, partner violence and community level violence. In one recent study, we analyzed Twitter language to uncover risk factors for community-level opioid overdoses. Our language analysis showed the language most predictive of opioid overdose was not explicitly about drug use, but was about physical and mental pain, boredom, and long work hours. Terms that indicated protective factors included wellness, travel, and fun activities.

psychological self-report data. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):9027. Published 2023 Jun 3. do: 10.1038/41598-023-34468-2

Q. What made you an early technology adopter?

I grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, which is a very poor area with high levels of crime. I had the idea that I could build technology to help. I’ve always wanted to deliver personalized digital interventions. Once you build that kind of tool, it can be cheap to disseminate. The goal was always to give back to communities that are low-resource or underfunded.

I started off by making a computer program while I was in graduate school to spread information about HIV and pregnancy prevention in Chicago, in the Cabrini-Green projects. It cost just 10 cents per CD to copy. We handed it out to any kid or community center that wanted it. It used a decision-making algorithm; a person would answer questions and get tailored messages in response. We didn’t call it AI back then—we called it math.

Q. Fast-forward to your current work. What might next-generation treatment and recovery programs look like?

We are working on using predictive data from smartphone use and wearable devices to develop personalized interventions. These tools will not replace treatment, just complement it. For example, a smartphone app could assess when someone is having an alcohol craving or having a high stress moment. There are nudges it could do based on user preference. It could start to play a favorite song or send a funny video clip or initiate a text message with someone the person has said they want to talk to when they're feeling stressed. As these AI models improve, we will soon be able to make very close to real-time predictions of user needs, and I’m loving it.

Q. Many see AI as scary for its disruptive potential, but you’re diving right in.

Yes, there is a lot of trepidation out there about potential uses. We are taking a hard look at things within our domain of expertise. But people thought the printing press was scary. The telephone was scary. Letting people learn to read or write was scary. But technology will change society, and it should change society. And NIDA can have a voice in using and improving technology. We can use it to dispense large amounts of information quickly, and we can use it to help treatment and healthcare be more efficient and effective.